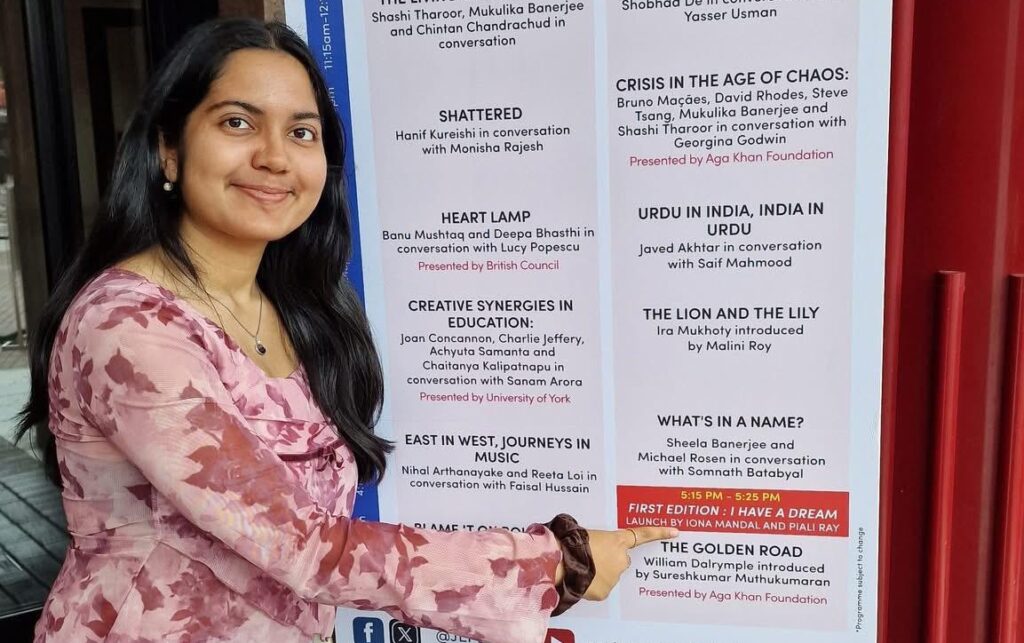

We were delighted to launch our latest book, a collation of young people’s work across Birmingham, UK and India, as part of the Jaipur Literature Festival at the British Library last weekend.

In I Have A Dream the younger generation use their voice to advocate for peace, love and community, their belief in equality and a better tomorrow spanning the 4,000 miles that part them. The book was launched by Piali Ray and Iona Mandal, young poet laureate 2022-2024. Printed below is Iona’s speech celebrating the launch…

Firstly, I’d like to express my gratitude to Mrs Piali Ray, Sampad, and Jaipur Literature Festival for allowing me to share this platform with so many inspirational voices. It’s an immense honour, especially as someone who still very much considers herself an amateur in comparison to the brilliant writers and thinkers gathered here today.

As a young person, it means the world to be reminded that our voices matter, that our dreams are worth listening to and that our words have weight. And that’s exactly what the book we’re launching today—I Have A Dream—seeks to affirm. It’s a collection of writing from students across India and Birmingham, and it stands as living proof that young people are not only paying attention to the world around them but are actively imagining how to remake it.

For me, literature was never treated as a distant, elite luxury. It existed in ubiquity, from the shelves of our family home to the library my mother took me to every day as a toddler. Books formed the quiet architecture of my childhood. They weren’t ornamental. They were ordinary, woven into the fabric of everyday life—and yet, offered extraordinary escape routes.

My family migrated from India when I was two years old, and as a child, I floated in a strange in-between for a while, without words. I couldn’t yet speak English and I hadn’t learned Bengali, since I had grown up in Bangalore, and only knew a few phrases of Kannada, yet nothing I could verbally communicate with to those around me. I existed in a kind of silence. I remember being painfully shy, almost paralysed by the fear of speaking. I would burst into tears if anyone unfamiliar spoke to me and in certain settings, I was almost entirely mute.

My parents began to proactively speak English at home, and language slowly began to take root. Still, it was books—quiet, patient, and forgiving—that taught me how to make sense of the world around me, and eventually, the world within. Reading gave me the tools to map my own interiority. I read about characters whose lives were starkly different to my own, but in them I saw pieces of myself. Books taught me empathy before I even knew the word for it and became my lifeline.

Coming from a South Asian immigrant family, I’ve always been aware that literature isn’t always seen as a practical pursuit.

There’s a quiet, well-intentioned fear in many of our communities—a fear that art won’t feed you, that writing won’t get you very far, that dreaming is a luxury only some can afford.

I understand that this fear comes from love, and generations who endured insecurity so we wouldn’t have to.

But my parents—while conscious of those fears—refused to limit my imagination. They encouraged and ignited it through reconnecting me with my roots: a vast and rich repertoire of Bengali literature. I remember the first book I bought in Brick Lane which helped me learn how to read and write the curlicues of my mother tongue, those volumes with soft covers and faded spines, holding the poetry of a language I was still learning to love. Those books taught me that my mother tongue was not an additional burden, but a gift and a foundation which eventually allowed me to write my own poetry, but also translate Bangla poetry into English—not just to share the beauty of it with others, but to affirm that both languages could coexist within me, each enriching the other. And now, as a first year English student at Oxford, I’m grateful to be able to apply these skills of translating literature across cultural contexts to my degree.

That’s why this book, the title of which of course intertextually echoes Martin Luther King’s famous speech, feels especially powerful to me. It stands as a bridge between continents, cities, and modes of thought, connecting the imaginations of young people in India and in Birmingham, the city I call home. And through their words, we see that imagination is not bound by geography, race, or class. These young writers are not just dreaming about their personal futures, they’re envisioning what the world could look like. And that’s incredibly radical in a world which often threatens the very act of imagining anything beyond profit and productivity.

Where dreams can feel like a luxury, these young writers remind us that dreaming is a form of resistance.

Through their words, they are sketching out new possibilities and I am proud that this book helps to hold space for that.

I hope this book reminds us that storytelling is a kind of seed-planting. That words—especially when they come from the hearts and minds of young people—can cultivate new ways of thinking, being, and becoming. And I’m so proud that we are using language not just to describe the world as it is, but to nurture the dreams of what it could be.